Learning Objectives¶

Theory / Be able to explain ...¶

- How modules, classes, and functions facilitate code reuse

- The parts of a function definition

- The logic of blocks, conditions, and loops

Skills / Know how to ...¶

- import and use modules (and classes, functions, etc.)

- Use dot notation to refer to an object's data and methods

- Define a function

- Write if statements in their many variants

- Write for loops and while loops

Three Kinds of Programming Structures¶

- Static structure refers to how the code itself is organized and assembled into software

- Control structure refers to programming logic (i.e., processing) used to tell the computer what to do

- Data structure refers to the way data is used, stored, and organized

We'll cover a bit of the first two tonight, leaving data structures for next week.

Libraries and Modules¶

- Turtle Graphics (chapters 3 and 4) is a library for drawing line art on an area of the screen (called the canvas).

- A library is a collection of reusable python code, organized into one or more modules.

- Modules are files (whose names end in

.py) with variables, callable functions and other reusable code.- We

importmodules to (re)use the code in our own programs.

- We

Standard vs Custom vs Third-Party¶

Libraries (and modules) come in three flavors:

- Standard Library modules are built into Python

- You may need to import them but you can count on them to be installed

- Custom modules are written by you for your use

- Source code kept in a folder (library) on your hard drive

- Third-Party modules must be installed in order to use them

- We can use a package manager like

piporcondato download and install them - Once installed they work like standard libraries and be used anywhere in your code

- We can use a package manager like

A Simple Turtle Graphics Program¶

import turtle # use the turtle library

wn = turtle.Screen() # creates a graphics window

alex = turtle.Turtle() # create a turtle named alex

alex.forward(150) # tell alex to go forward 150 units

alex.left(90) # tell alex to turn by 90 degrees

alex.forward(75) # continues on (upward) ...

Classes, Objects, and Methods¶

A class is a data type that defines ...

- What kind of data is stored and how it is organized

- What kinds of operations can be applied to the data

Each data type in Python (even built-in ones like int or float) is actually a class.

An object is an instance of a class (data type)

- The operations we can apply to the data are called methods.

- An object can bundle together multiple data values (of different types) as instance variables

- The current value of an object’s data is called its state.

Each data value in Python is actually an object.

Dot Notation¶

To invoke (or call) a method of an object (literal value or variable reference), we tack on a dot (period) followed by the method call. The method calls always know what objects they are attached to.

<object>.<method call># Examples with string objects (instances)

"ZXYW".lower() # method call on a string literal

alpha="abcd" # set a string variable

alpha.upper() # method call on string variable

# Examples with string objects (instances)

print("ZXYW".lower()) # method call on a string literal

alpha="abcd" # set a string variable

print(alpha.upper()) # method call on string variable

zxyw ABCD

Turtle Graphics Again¶

import turtle

wn = turtle.Screen()

alex = turtle.Turtle()

alex.forward(150)

alex.left(90)

alex.forward(75)

- A module is just a container object for classes, constants, variables, functions, etc.

- We access the various parts of the module using dot notation, just like any other object.

A Quick Digression on Functions as Objects¶

Functions are also objects. You can think of a function like an object with a single method that is executed every time the function is called. (There's more to it than that, of course ...)

# the following does not run without some work (not shown)

# but illustrates the "everything is an object" principle

add(1,2) # function call to add two numbers

1.add(2) # method call to add one number to another

# note that the number 1 is an object in Python

But first ... Definitions vs (other) Statements¶

A module is a .py file that contains a number of reusable Python definitions and statements

- Definitions specify classes (data types) and functions that can be used elsewhere

- Statements perform actions like defining variables, calling functions, etc.

We use import statements to integrate modules into our code. We then use dot notation to refer to any classes or functions defined by the module.

Function Definitions¶

A function definition encapsulates (Google that!) a block of code into a form that can be called by other code

def <name>(<parameters>):

<statements>

defindicates the start of a function definition<name>is the name of the function<parameters>is a comma-delimited list of input variables- The indented block of

<statements>comprise the body of the function - Any variables are local to the function body and have no effect elsewhere.

Take note: punctuation like indentation, spaces,:, ( and ) matter here. Don't ignore them!

Try It!¶

def add_two_numbers(x,y):

z=x+y

return z

add_two_numbers(1,2)

- The function name is

add_two_numbers - parameters

xandyact like variables within the body - local variable

zis undefined outside of the function body - The

returnstatement completes the function call and (optionally) provides a value - As always the body (block) is indicated with indentation

def add_two_numbers(x,y):

z=x+y

return z

add_two_numbers(1,2)

3

- Notice how Jupyter outputs the number 3 despite not being asked to print anything? By default, Jupyter displays the value of the last expression in a cell unless asked to print something else.

- Aside: Function calls pass arguments but function definitions define parameters.

- Confused yet?

- The arguments are data, while the parameters are variables.

Blocks¶

A block of code is just a series of statements that are run in the order given.

- In Python indentation is used to indicate statements within the same block. One or more statements in sequence with the same indentation are in the same block

- Individual statements can contain their own blocks, effectively nesting blocks inside one another (Inception-style)

gashouse_gang = ["Evers","Tinker","Chance"] # A block

for player in gashouse_gang: # with two statements

print(player) # A new block nested within

# the for statement

Evers Tinker Chance

x=1 # three statements

y=2 # in the same

print(x+y) # block

print(x+y) # another block

File "<ipython-input-3-91f4d40a6bfe>", line 4 print(x+y) # another block ^ IndentationError: unexpected indent

Why do you suppose we get this error?

Because indentation is part of the logic. It's illogical to start a new block for no reason. It needs to nest logically inside another statement.

Conditionals¶

Conditional execution allows a block to run only when given conditions are met.

Typical form is binary selection

if <boolean expression>:

<True block>

else:

<False block>

What's a boolean expression?¶

- a bit of code that evaluates to True or False

- we'll come back to this in a minute

Try it yourself¶

x=1

y=2

if x>y:

print("x is bigger than y")

else:

print("x is not bigger than y")

x=1

y=2

if x>y:

print("x is bigger than y")

else:

print("x is not bigger than y")

x is not bigger than y

Boolean Expressions¶

So what counts as a boolean expression?

- Literal values 0 (False) and 1 (True) or equivalents

- Relational comparisons:

x == y(is x equal to y?)x > y(is x greater than y?)x >= y(is x greater than or equal to y?)

- Logical composites of boolean expressions (with

and,or,not, and()operators):

((x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

Try it Yourself¶

x = 8

y = (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

print(y)

x = 8

y = (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

print(y)

False

Try other values of x. What values cause the expression to evaluate to True?

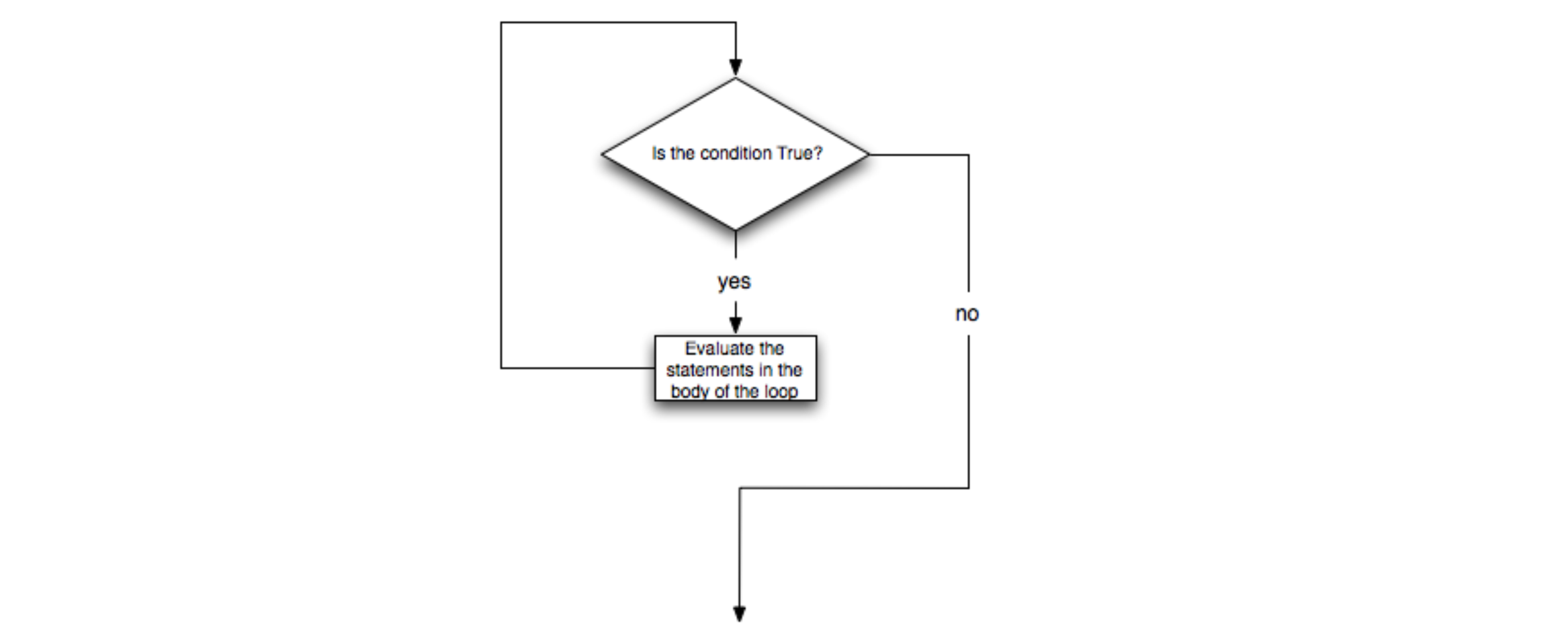

Loops¶

A loop repeats a block called the body over and over again until a termination condition is met.

- Our old friend the

forloop is great for iterating over a set of items - Sometimes we need to handle more complex logic, which leads us to the

whileloop

A Challenge¶

Write a for loop that tests each value of x between 0 and 16. For each value tested, print the value and whether (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15)) is true or false.

for x in range(17):

y = (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

print(x, y)

0 False 1 True 2 False 3 False 4 False 5 False 6 False 7 False 8 False 9 False 10 False 11 True 12 True 13 True 14 True 15 False 16 True

while Loops¶

while <boolean>:

<statements>

<boolean>is a condition to check at the start of each pass through the loop<statements>in the body are only executed when the condition is true; if the condition is false then execution skips to the statement immediately after the loop body

Pro Tip: The Accumulator Pattern¶

Anything you can do with a for loop, you can also do with a while loop (though in a slightly more verbose way) using an accumulator variable.

- Each pass through the loop updates one or more accumulator variables to reflect history to that point

- Accumulators can be anything: a number, a string, a list, etc.

- Often, but not always, the loop condition is based on the value of an accumulator variable

# The example for loop (again)

# for x in range(17):

# y = (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

# print(x, y)

# --------------------------------------------------------

# The equivalent while loop

#

x = 0 # initialize our accumulator x

while x < 17:

y = (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15))

print(x, y)

x = x + 1 # increment the accumulator each

# pass through the loop

0 False 1 True 2 False 3 False 4 False 5 False 6 False 7 False 8 False 9 False 10 False 11 True 12 True 13 True 14 True 15 False 16 True

And now let's take it to the next level¶

Use a while loop to find and print out the values of x (up to 16) such that (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15)) is true. Do not print out the values where it is false.

x=0

while x <= 16:

if (x == 1) or ((x > 10) and not (x == 15)):

print(x)

x = x + 1

1 11 12 13 14 16

We forgot to modify the accumulator variable x with every pass through the loop!

The test x<10 never returns False, so the loop never ends. This can actually crash your computer if the loop is part of your operating system code.

Classwork (Start here in class)¶

- Data Camp “Functions and Packages” assignment

- Health Stats Part 1

- If time permits, start in on your homework.

Homework (Do at home)¶

The following is due before class next week:

- Any remaining classwork from tonight

- RSI Chapters 9, 10, and 12

Please email chuntley@fairfield.edu if you have any problems or questions.